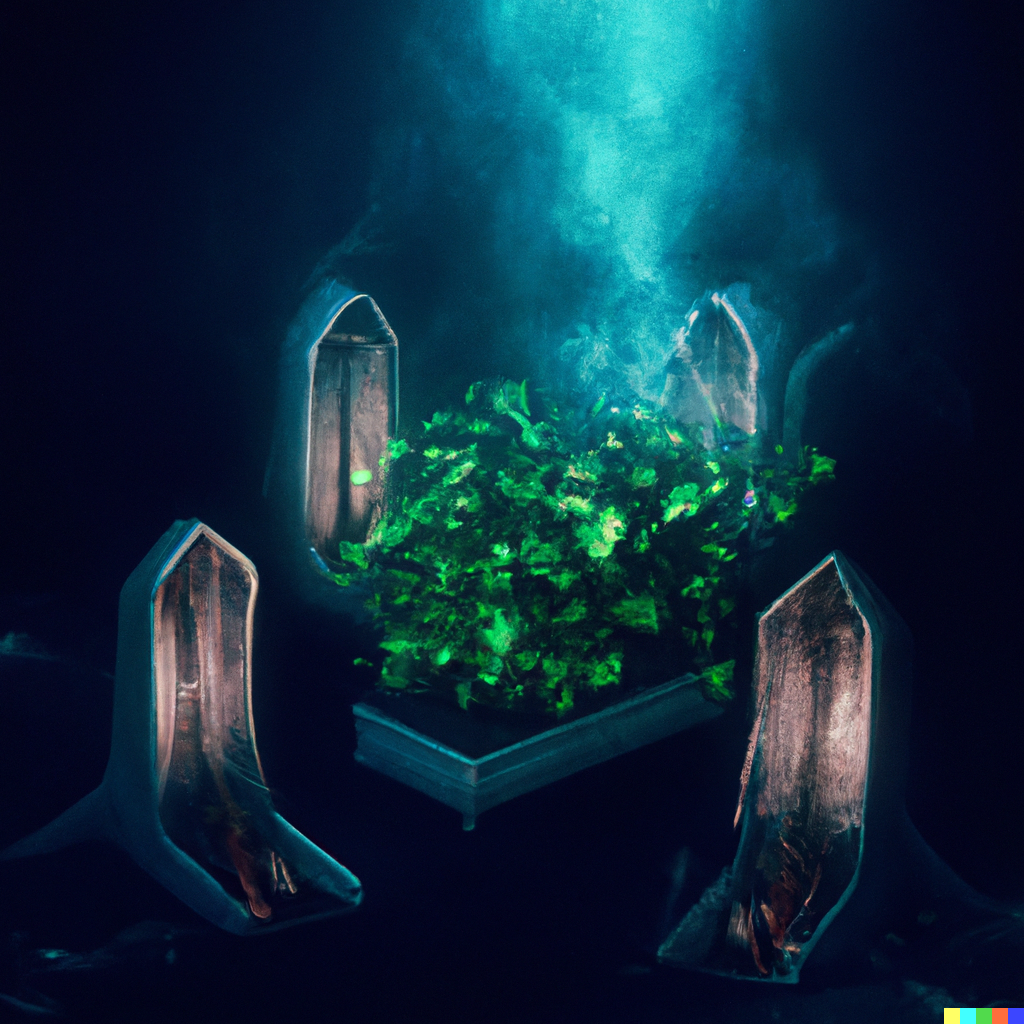

When I wrote The Doll, I had a vague idea of writing a few further stories about the doll soon, but had no clear idea of what I wanted to write about. But then I saw the above image, (or rather the original here) by Nazly Ahmed and a new story started taking shape in my head …

Many thanks to Nazly for his kind permission to use (and to modify) his photo to suit my story!

The red light atop the Lo’us tower blinked slowly like a baleful cyclops’ eye surveying all the destruction it had wrought. Jeera looked up at the blinking light, trying to gauge how much time he had before everything was swallowed by a cloak of darkness and fog. He’d always thought that the light glowed brighter as the footfalls of night approached.

He fancied that he could predict nightfall to the exact instant — his brothers had mocked him mercilessly the first few times he’d tentatively mentioned the possibility. They thought it was just another will-o’-the-wisp of his fancy. He’d kept his theories to himself since then.

Jeera hurried his steps. It didn’t do to get caught out here after nightfall. There were just too many stories about people who had seen strange and terrible things in these parts — huge, glowing serpents bearing iridescently glowing gems in their long, gleaming fangs; giants with gem-encrusted golden swords that shone as bright as the sun who could split mountains in two; monkey-faced devil-boys who threatened to kill you unless you kept them constantly busy with new tasks to be completed [probably where the phrase “monkey-on-your back” came from]; impossibly beautiful ladies clad all in pristine white who would ask you for help, but if you stopped to help, would then turn into she-demons who sucked your brains out; that kind of thing.

Jeera sucked in his breath and stopped dead in his tracks. There was a shadowy figure behind one of the huge trees in the area! Could that perhaps be the aforementioned lady in white? He was half-fearful, half-hopeful — he’d never seen pure white in this dirty world he inhabited.

He peered closer through the gathering gloom, and then breathed a sigh of relief — it was just an Ai Hondai Aunty!

The Ai Hondai Aunthood had been a community fixture since time immemorial. They said that the Aunthood had originally started way before the Great Woe as a different organization, the Baane Gedharata network. It had been composed of mothers (and mothers-in-law) who got together to get their inebriated sons-in-law home safely so that their daughters would not worry.

Then the Great Woe had come and everything had fallen apart. But the network of mothers had stood firm, being the proverbial rock, amidst the chaos of the age. They’d organized each neighbourhood to survive on their own, given guidance, tended to the wounded, and provided the advice and direction that the shattered communities needed to get some semblance of order and normalcy back.

Everyone and their dog — or cat — called them Aunty and the fact that they always inquired after your well-being had resulted in the network’s original name changing over time to Ai Hondai Aunties.

Everything changes over time. As people had grown accustomed to the Great Woe, life — which had fallen off the smooth and speedy highway it had been on and into the wayside the ditch — continued to move forward in the ditch at a slower pace. The Ai Hondai Aunties had networked across communities and become more powerful. They controlled everything, and knew everything that was going on everywhere.

Jeera did not want the Ai Hondai Aunty getting all in his business. He had no business being here at this time, and he intended to keep it that way. Had she seen him?

He peered through the soupy smog and breathed a sigh of relief. It didn’t look as if she had seen him. She was busy hacking away at a bush — perhaps she was out gathering ingredients for one of the foul concoctions that the Aunthood gave out for all and sundry ailments?

He backed away slowly, making sure that he didn’t step on any dry branches or twigs that might alert the Aunty as to his presence. He was so busy trying to make sure that the Ai Hondai Aunty didn’t see him that he forgot to looking where he was heading. Of course, not having eyes on the back of his didn’t help with matters much either.

He felt his back come into hard contact with something and almost screamed. Almost. Stifling the scream, Jeera turned around. It was one of the metal trees from back in the day — the ones that didn’t grow any taller or put out any new branches.

He shrugged dismissively and would have moved on if something hadn’t caught his eye. Hang on, what was that hanging on the tree? He looked closer and almost screamed again when he saw the doll.

The doll was just hanging there, moving to and fro slowly with every gust of wind. The empty, dead-eyed stare of the doll reminded him of the monkey-faced devil-boy stories. Was this some apparition? Or just something some stupid kid had hung there to scare people? He moved closer to the doll to get a better look.

And then the doll spoke.

Well, it didn’t really speak as such. After all, the doll didn’t have movable lips and probably none of the internal bits needed to speak, right? But he heard a voice inside his head that seemed to bypass his ears and went straight through to his mind, or whatever he had that passed for a mind, within his cranium.

It said, “Hello!”

Had it really said “Hello”? Or had that been his fears taking hold of his mind and addling it?

“Hello?”, said the voice again.

Jeera decided to take a chance on his state-of-mind meter not having hit “insane” and decided to respond.

“Hello?” he said tentatively.

“Ah, I wasn’t sure if you could hear me!”

“Well, that makes two of us! I wasn’t sure that I was hearing you either,” said Jeera, still wondering if this was real, or if he was at the cozy little rubble heap that passed for his home and just dreaming a really vivid dream.

“I’ve tried to talk to several people, but you were the first one to hear me.” said the voice as if a doll talking to people was the most natural thing in the world.

“If you wanted to talk to people, then you should have chosen a place with well … more people, don’t you think?” asked Jeera.

The doll sighed. Or at least, that’s what it felt like in Jeera’s head.

“Yes, that would have been the thing, right? But it appears that I made a bit of a calculation error when I beamed myself here.”

Jeera wondered again if he should try to pinch himself. He’d heard that you can pinch yourself in a dream to see if you were awake or not. But he didn’t really understand what that would prove. Did you actually pinch yourself when you thought you pinched yourself in a dream? Or was it a dream pinch where you didn’t feel anything?

That line of thought seemed to be fraught with logical traps and pitfalls and Jeera had never been one to indulge in much philosophical thought anyway. So he decided to get back to what was right in front of him — the doll.

“Umm … OK. So what do you mean ‘beamed’. And who are you?”

“I am an emissary from what you would call an alien race …”

“Alien? You mean like Yindians?” asked Jeera, the blood pounding through his heart like a herd of helliphants rushing through the streets. His mind swam with visions of the terrifying Yindians he had been taught to beware of since a young child. Apparently, there were two types — the Yindians and the Yandians and they …

“No, no, not like that!” said the doll, breaking in on his terrified mental accounting of the Yindians and all the accompanying horrors. “I am from a different planet, a race of beings from across the stars…”

“So all your people are dolls where you come from?” asked Jeera, his mind trying to grapple with this new concept — when you’re a half-wit, this wasn’t an endeavour you wanted to engage in.

“No, you id.. I mean, no, we are not dolls where we come from. We are incorporeal beings. But our planet is very different to yours. Here, on your planet, we have to be contained in some sort of vessel for us to exist. So I beamed myself into this doll.”

“Ah, they stuffed you into the doll!”, exclaimed Jeera as the blazing light of understanding slowly — oh, very slowly — penetrated the congealing darkness that was his mind.

The doll seemed to sigh again. “Yes, let’s call it that. I came here to let you know something very important!”

Ah, this was all making sense now, thought Jeera. “What?”

“What do you mean what?” asked the doll, sounding irritated.

“What is the important thing you said you had to tell me?” asked Jeera, slowly enunciating each word, exasperated. The doll was a raving idiot!

“Well, you see, it’s a bit of a long story. We have been observing your planet and your race for millennia. We were there when your race burnt and ravaged their way into dominance on the planet. We watched when you started killing each other for trivial things and started great wars. We still watched as you destroyed your planet by poisoning all that you needed to survive with not a thought for the future of your race …”

“OK, so you’ve been watching us for a long time,” replied Jeera, cutting in on the doll’s droning voice. “But what’s that got to do with me?”

“I’m getting to that,” said the doll, sounding irritated again. “My people like to observe and learn from other races across the galaxy. But they will not interfere with a race in any way.”

The doll paused for a moment, as if gathering its thoughts. “However, your race is in a unique situation that I think requires a change in our policy of non-interference…”

“What do you mean?”

“You see, your sun will go super-nova soon…”

“My son? I don’t have a son …” replied Jeera, wondering if perhaps the doll had mistaken him for someone else.

“Not your son! I meant the sun in the sky, that yellow, fiery, ball in the sky giving off light and heat!” The doll paused for a moment, as if catching itself, “Well, at least, it used to provide light and warmth before you polluted things so badly that it looks like dusk during mid-day down here!”

The doll seemed to be exasperated. This was common for anybody who tried to carry on a conversation with Jeera for any length of time. Jeera was used to it. He just nodded sagely as if he understood everything — that always seemed to work. But he idly wondered what the sun had to do with anything …

“Your sun is going to explode soon,” said the doll, seeming to calm down a bit. “And when it does, it will destroy your planet and all of your race.”

“What? Are you sure?” asked Jeera.

“Of course I’m sure!” snapped the doll. “We’ve been monitoring your sun for centuries. We know it will happen. Very soon. But my people don’t want to do anything to save yours and that’s why I’m here.”

“Why don’t they want to save us?” asked Jeera.

“Well, first there’s the whole non-interference thing. But then there’s the whole issue of your race …”

“What about my race?” asked Jeera, bristling on behalf of humanity.

“Do you know much about what you call the Great Woe?” asked the doll.

“No, not really. Something bad happened way back in time and everything went wrong. I thought it must have been a war or something.” replied Jeera. “Before that everything was so good they say. Everybody had as much food as they wanted, they had flying cars, whatever those are, and everybody lived in palaces …”

“It was never quite like that. Your people are very short-sighted and they grew more and more self-centred as they mastered the planet and their environment. Sure, some had much easier lives, and grand buildings, and lives of ease. But there was a significant portion of your population who lived very much as you live now …”

“That can’t be true!”

“And yet, it was. Your people grew so complacent that the time before the Great Woe was a time where lies were accepted without any hesitation, but truth had to do battle in the court of public opinion just to survive, and still often lost.”

“What’s that got to do with anything?”

“That’s what led to your people’s undoing. You gave charlatans and carpetbaggers the mandate to rule you because they promised much. And yet, when given the chance, they ended up delivering little and enriched themselves at the cost of the people. Your people did this over and over again as if believing the scoundrels a second time would lead to different results.”

“One of your philosophers — or was it a scientist? — said that doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results was the definition of insanity. And he, or she, wasn’t wrong.”

“Then you were hit by the Great Woe. Nature, which had been ravaged and desecrated by your people without any thought or care for so long, seemed to rise up against your people with a vengeance. Typhoons, tornadoes, earthquakes, floods, and tsunamis became the norm. Roads, bridges, and any means of connection between communities were washed away or buried under tons of rubble.”

Jeera listened, half-enthralled, half-horrified. He wanted to say something that would stop the flow of words from the doll, but he didn’t know what to say.

“Each continent, country, city, cantonment, cohort, cabal, or cluster wanted to hoard food, energy, water, medicine, and other essentials, or even non-essentials, for themselves. Keeping everything for themselves and sharing nothing with their neighbours. Isolationism grew like mold in a petri dish.”

“The politicians you trusted and believed in deserted you. They ran into their hide-y-holes like rats scurrying to safety. The general populace was left to fend for themselves. And that’s where you are today.”

“Basically, my people think that your people are infected with a form of collective insanity. You don’t want to think for yourselves individually. Instead, you want someone else to do your thinking for you and to tell you what you should do. You accept the collective consensus even if the collective is wrong.”

“And this is the second thing that prevents my people from wanting to help your people. They don’t want this insanity spreading through the rest of the universe.”

The doll paused and Jeera figured that he had to say something. Thoughts swirled through his head, more numerous than the nits and lice picking away at his scalp. He wanted to ask why the doll wanted to help them, what could be done, where the politicians had gone, and so many more unverbalized thoughts, questions, and emotions …

But at that moment, there was a noise behind him that startled him. He turned around hastily just as something flew by his head and landed on the doll. Jeera turned back just in time to see some sort of liquid landing on the doll. The doll began melting and dripping slowly down to the ground like the wax from a lit candle.

The last words he heard from the doll were, “Ugh, humans!” before it went silent.

He turned back to see an Ai Hondai Aunty. Perhaps the same one he’d avoided just a little while ago? She looked at him sternly, even accusingly.

“It’s a good thing I came along,” she screeched at him. “I saw you standing there, talking to yourself. That thing’s probably a hoodoo charm. Or maybe even a demon. Good thing I had my demon warding potions with me. Otherwise who knows what the demon would have done to you?”

Jeera struggled for words. Tried to find a way to explain all that had happened to the Ai Hondai Aunt. But what was he to tell her? Would she even believe him? Or would she think that he was mad — or worse yet, possessed — and try to cure him?

The Aunt glared at him. “Don’t you know you are not supposed to be here at this time! How many times do I have to tell you youngsters to stay away from the bad places! Go on before I drag you in front of the council!”

Jeera grinned weakly at the Aunt, bobbed his head quickly, and walked away as fast as he could from her. What else was he to do?

A tiny corner of his mind wondered if the doll had spoken the truth? Would the world be destroyed tomorrow? He shrugged it off. Tomorrow was another day and who knew what might happen tomorrow?